Welcome to

benjaminhoffauthor.com

The only official website –- and, in all probability, the only factually correct website –- for the author Benjamin Hoff.

On March 13, 2012, my mother died in Milwaukie, Oregon, a few weeks before her 102nd birthday. The following text is the essay about her that I read at the March 31st memorial service, preceded by my introductory remarks.

B.H.

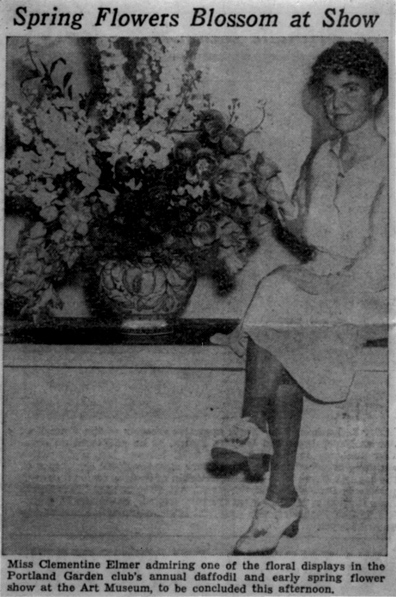

Clementine E. Hoff

April 27, 1910 - March 13, 2012

When I was visiting my mother one day in the summer of 1997, I noticed on her coffee table an opened envelope with a folded letter sticking out. The publisher name above the return address caught my eye: Marquis Who’s Who. I pulled the letter out and read it.

“These people want to list you in Who’s Who of American Women!” I exclaimed, telling her what she apparently already knew. “Oh, I don’t care about that!” she replied. And so, as she was fond of saying, that was that.

A couple of years ago, when my sister and I were going through Mother’s effects in preparation for the family estate sale, I found that letter. On its envelope, postmarked June 24, 1997, were these words in Mother’s handwriting: I did not respond. I’ve kept the letter. And although nothing ever came of it, at least I can say that my mother was almost listed in Who’s Who of American Women.

When I started thinking about what I could write down to say about Mother for this memorial service, I imagined discussing with her which incidents in her life I would like to cover. I immediately knew what she would say: “Oh, don’t talk about me!” Then I would reply, “But this is for your memorial service. I’ll have to talk about you -- that’s the whole point of the thing!” She would think for a bit and then say, “Well, then, talk about what I believed in.” So that’s what I decided to do.

I’ve chosen to begin what I have to say about my mother, Clementine Elmer Hoff, by telling of an incident in the life of her mother, Clementine Catlin Elmer. The incident illustrates an attitude that my mother inherited from her Catlin-and-Elmer parentage, an attitude that she passed on in turn to her own children.

My grandmother was the wife of William Wells Elmer, a mining engineer. At the time of this episode, my mother hadn’t yet been born and her young parents-to-be were living in Mexico on a hacienda provided by the mine owner Grandfather was working for.

One day when Grandmother was taking a walk around the hacienda grounds, she came upon some field hands blasting away with their pistolas at tin cans lined up along the top rail of a distance fence. Grandmother, who deplored any waste of time, materials, or skills, asked the workers why they were wasting all three shooting at the cans -- a good many of which they were failing to hit. “We must practice our marksmanship, Senora Elmer,” one of them insisted, “so we can kill the varmints that invade the property. As you can see by the cans we have missed, we need to practice this shooting.” “Well, it doesn’t look very difficult to me,” Grandmother remarked, studying the distant targets.

On hearing this, one of the hands became a bit overheated. He loaded the six chambers of his pistola and handed the revolver to Grandmother. “Perhaps Senora Elmer could do better,” he challenged her. Another worker lined up six cans on the fence.

Grandmother hated guns and had only learned to use them because Grandfather had insisted on teaching her. But she raised the pistol, took careful aim, and fired: bang -- shot the first can; bang -- shot the second can; bang -- shot the third can; bang -- shot the fourth can; bang -- shot the fifth can; bang -- shot the sixth can.

She handed the empty pistola back to the worker and walked on, leaving him and his fellow field hands staring at the fallen cans.

Grandmother would never have mentioned this little episode -- to have done so would have gone against her nature. But there were witnesses… And from them, the amusing incident became known to my grandfather.

My grandmother’s attitude toward any such test of ability was: We must do our best in this world, with no wavering and no excuses – but let’s not make a big thing of it. That was my mother’s attitude as well.

Aside from her own work as an artist. Mother taught adult and children’s classes in drawing and painting, and was Director of Children’s Classes at Portland’s Museum Art School from 1942 to 1946, resigning when I was about to be born. Her paintings were exhibited at the Portland Art Museum and the Seattle Art Museum. She also made a painting or two for the government’s WPA, or Work Projects Administration.

Mother was part of what’s known as “Old Portland” -- she was of the Henderson family, a branch of the Failing family, one of the families that founded Portland. Her earlier-generation first-cousin-once-removed, Henrietta Failing, had been the first curator of the Portland Art Museum. Mother was a member of what was informally and humorously known as “the Harry Wentz set,” an art-and-hiking circle of friends that included the late, now internationally renowned architect Pietro Belluschi, who designed the Portland Art Museum’s present main building.

Mother was part of what’s known as “Old Portland” -- she was of the Henderson family, a branch of the Failing family, one of the families that founded Portland. Her earlier-generation first-cousin-once-removed, Henrietta Failing, had been the first curator of the Portland Art Museum. Mother was a member of what was informally and humorously known as “the Harry Wentz set,” an art-and-hiking circle of friends that included the late, now internationally renowned architect Pietro Belluschi, who designed the Portland Art Museum’s present main building.

Several years ago, I took Mother to an Art Museum exhibition. After we’d looked at the main displays, she left me to see what was being shown in the back galleries. A few minutes later, she returned, walking arm-in-arm with an elderly but still handsome man, whom I recognized from photographs I’d seen. Both of them were grinning like children. “Pietro,” Mother said to her old hiking companion, “this is my son. Ben, this is my dear friend, Pietro Belluschi.”

As a child, I was introduced by Mother to a good many other luminaries of the Pacific Northwest art world. The only ones I remember clearly were Anna Crocker and Harry Wentz.

Today I know by what I’ve read that Anna B. Crocker, a graduate of New York’s Art Students League, had been appointed to the dual position of museum curator and school principal at the Portland Art Museum, replacing Henrietta Failing on her retirement. She remained the curator and effective director for twenty-seven years. She was best known for her teaching brilliance, her paintings -- two of which remain in our family’s possession -- and her extensive studies of European art museums.

Harry Wentz, I’ve read, was the most important influence on Portland artists during the first half of the twentieth century. Educated at the Art Students League, Columbia University, and various universities in Europe, he achieved over the years of his life such an impressive number of accomplishments and credentials that it would take me twenty minutes to describe only the major ones. Instead of attempting such a thing I’ll read a sentence about him written by Pietro Belluschi: “His greatness rests on the uncompromising integrity of his whole life, the humanity of his responses, on his intolerance of anything superficial, and his ability to detect instantly fraud or insincerity in people or their works.”

As a child, I knew Miss Crocker only as an elderly woman who lived in a Victorian house near Macadam Avenue, who made delicious frozen desserts for us very young children, my sister Laurie and me. Mr. Wentz, of whom I still have some snapshots, I remember as a kind old man who well understood children, and who had a large sea chest filled with the most marvelous wooden toys I’ve ever seen, which became the inspiration for my own wooden toy collection.

Even at a young age, I sensed that these two people, and other art-world figures to whom I was introduced, were important -- and secure enough within themselves that they had no need to prove their importance.

One individual who did seem to think she had to prove her own greatness was Mother’s nemesis at the Art Museum, with whom I myself sometimes came in contact in the two years I attended the Museum Art School. Mother’s philosophy on art was: work. Her opposite number’s philosophy was: grandstand – give radio broadcasts, arrange art gatherings with important people, provide plenty of photo opportunities… To Mother, this was all showboating and self-aggrandizement. She wanted to help other people develop skills and character; she had no interest in what she considered pink teas and grandstanding. She believed that the arts were vital for developing and teaching practical observational and listening skills, as well as for promoting creative reasoning. To her these things were what mattered. Her attitude was: Let the showboaters do their showboating. But just remember that in order for them to have a finished piece of art for them to showboat with, someone first has to do some work.

Mother was, I believe it could be said, the last survivor of generations of accomplished Portland artists with a roll-up-your-sleeves-and-get-to-it attitude toward art, and a strong focus on the natural world and its relevance to humanity. Both the museum and the school have taken very different philosophical roads from those of her time. I don’t believe that her death marks the end of an era, though, because I think that, as far as the Portland art world is concerned, that era ended two or three decades ago.

Some years back, my sister and I took Mother to an exhibition at the Pacific Northwest College of Art, formerly the Museum Art School. After we’d looked at the displays for a while, I wandered over to a hallway and noticed some photographs on the wall with a printed query: Can you identify any of these people? The photographs, I saw, were of early days at the Museum Art School. Following the query was a statement to the effect that the school was preparing for its centennial celebration, then a few years in the future, and that it would like to be able to say who the people in the photos were.

I took Mother to the photographs. “Oh, yes,” she said, pointing to an individual, “that one is Louis Bunce. He was one of my adult students for a while. I was always saying, ‘Louis, why don’t you develop your own style, instead of imitating other artists?’ But eventually he did.” She identified one face after another.

I went to the young man at the entrance desk. “My mother used to teach at the Museum Art School,” I told him, “and she’s back in the hallway now, identifying a lot of the mystery people in the old photographs. Is there someone we could talk to about that?” “Not at the moment,” I was told. “Well, then,” I said, “maybe someone from the school would like to interview her sometime. She remembers a lot about the school, and its history.” I gave the desk attendant my name and phone number.

Months later, after no one from the school had called, I phoned the school and was connected to someone official, to whom I elaborated on what I’d told the desk attendant about Mother being able to identify people in the photographs. The woman took my name and phone number. No one called. I later repeated the process with two other officials at the school. No one called.

The school, I am told, has changed greatly from the one I attended, and the school as Mother knew it. “Art as technology and artists as technicians” would sum up what I’ve been told. Perhaps that’s a misleading description. I hope so. But the fact that no one I talked with at the school did as much as say “Hello” to Mother, let alone ask her anything about the school’s past, would seem to indicate otherwise.

I think that what made Mother even sadder than seeing all her art friends leave this world was seeing art and music education eliminated from American public and private schools. America has thrown the arts out of education in favor or science and math, which the educational powers-that-be consider vital skills. These authorities seem to lack observational ability. They don’t seem to have noticed that as the arts have been expelled from school, American students’ science and math skills and comprehension have fallen in worldwide achievement tests and contests. We are now consistently far down in the rankings in all of the international science-and-math arenas of scholastic achievement-testing. Just as significant, and just as overlooked by our educational system's directors, is the fact that the nations whose students score higher than ours in science and math are being educated by school systems that strongly emphasize art and music. And the very highest-scoring science and math students are from nations that base their education on art and music. I might add that, as a former “A” student in classes in advanced biology, I can myself attest to the scientific benefits of an upbringing in the arts.

It’s not only our educational system that has lost its way regarding creative skills and reasoning. Recent reports tell us that the American economy is now seventy-five percent consumer driven. That means that as long as we Americans keep spending our money, even if we have to go into debt in order to do so, our economy appears healthy -- but when we stop spending, the economy crashes. We are no longer a producing society -- a manufacturing society, an inventing society, a creating society -- we are now overwhelmingly a society that buys what other societies make. Our long-acclaimed “Yankee ingenuity” is rapidly becoming a thing of the past, as both Europe and Asia out-clever us and out-create us.

In this-way-and-that, Mother said that without creative thinking and observational skills, such as are developed in the practice of art, it is very difficult to achieve much of anything of positive, lasting significance in this world. What I learned from her, and from my father -- both practicing artists -- is to observe things exactly as they are… and then make them better. I could not have had a more valuable inheritance.

Benjamin Hoff